WTP, or DIY Pho

fig. a: 1/2 photo

fig. a: 1/2 photo

Those of us who've never been might find this hard to imagine, but, as David Tanis points out in Heart of the Artichoke (Artisan, 2010), "In Vietnam, pho is street food, basic, hearty, and filling, sold from a cart with a few little stools in front."* In the United States, on the other hand, pho is generally available from "little bare-bones sit-down restaurants," Tanis continues, places where you can grab a quick but satisfying lunch or dinner. Many of us have never had the pleasure of having pho as street food, but we're well-acquainted with the kind of no-frills pho joints he describes, because you can find them in many places around the world these days.** Montreal, for one. Paris, for another. And, in fact, that's exactly where Tanis first became fully enamored of Vietnamese cuisine--not in the United States, not in Vietnam, even, but in Paris.

He writes:

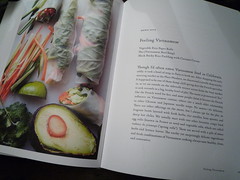

Though I'd often eaten Vietnamese food in California, oddly, it took a bowl of soup in Paris to hook me. After shopping the early morning market at the Place Maubert, we discovered a noodle shop nearby. It happened to be one of those damp, chill spring days the French specialize in, so we sat outside on the sidewalk terrace across from the busy market to seek warmth in a big, brothy bowl of pho.

Tanis doesn't elaborate, but there was something about that bowl of soup on that particular day that really clicked with him. So much so, that, years later, he'd devote an entire menu to Vietnamese cuisine in one of his cookbooks. And, sure enough, the central attraction in Tanis' homage to Vietnam in Heart of the Artichoke is his take on pho bo, the classic Vietnamese beef and noodle soup.

Now, the funny thing is, we first became enamored of David Tanis back in 2005, when he was featured in an article in Saveur ("An American Cooks in Paris" by Dorothy Kalins, #88). The concept was simple. Tanis was introduced as one of the chefs at Berkeley's legendary Chez Panisse (which he was and continues to be), albeit one who spent six months of the year in Paris, during which time he and his partner ran an underground restaurant, Aux Chiens Lunatiques. Who better to give Saveur's readers a tour of Paris's markets and a crash-course in how to make use of the bounty? The resultant spread was beautiful (photos by Christopher Hirsheimer!), highly informative, and utterly seductive (foie gras pâté! sautéed wild mushrooms! roast pork with fennel, garlic, and herbs!), and one of his dishes, his wonderful swiss chard gratin, became an AEB standard. But one of the things we liked best about Tanis, was that he began his Parisian shopping excursion by taking the author out for a "restorative bowl of beef pho at his favorite neighborhood Vietnamese place." This was a man we could totally relate to, a man after our own hearts. But the important thing here is that Tanis didn't make his bowl of beef pho, he went out to his favorite pho joint and bought it, and the article focused on French recipes made with French ingredients.

It took us a while to get around to making our own bowl of homemade pho. It took Tanis's Heart of the Artichoke + a trip to visit our friends S & T in Upstate New York. It's not that it had never occurred to us. We love Vietnamese food, and we've made our fair share of Vietnamese food at home, including a few soups. But we live in a city where pho joints abound, and many of them are quite good, so when we cooked Vietnamese, we often made things that were less readily available. Plus, we, like Tanis, really like going to pho joints, especially when we're out on one of our shopping excursions. Hell, that's exactly how "...an endless banquet" got started, way back when.

But there are times when you're not in Montreal or Paris, or anyone of a number of other places where Vietnamese restaurants are plentiful (Berkeley, New York, Chicago, Arlington, Toronto--take your pick).

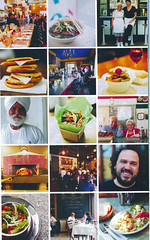

fig. b: time for pho

fig. b: time for phoThere are times when you're in the countryside--in Upstate New York, perhaps--hundreds of miles from the nearest pho joint, and you've been traipsing around in the snow all day, and a restorative bowl of pho sure would taste good.*** There are times when your curiosity gets the best of you ("How do they make that broth?"). And there are times when you want a lot of pho--enough for leftovers, enough to stock your freezer, enough that you might actually be able to try it for breakfast (like you're supposed to) sometime. For all those times, it's nice to have a pho bo recipe you can really trust. Plus, as Andrea Nguyen puts it in Into the Vietnamese Kitchen, "Despite the fun and convenience of eating pho at a local noodle soup spot, nothing beats a homemade bowl." Why? Because it's all about the broth, and at home you can put all the care and attention you want into making your pho especially rich and tasty.

fig. c: photo #2

fig. c: photo #2So that's exactly what we did. We broke out Tanis's Heart of the Artichoke, flipped it to his "Feeling Vietnamese" menu, and got to work. S & T had taken care of getting all the ingredients ahead of time, back in the Big City, so we were good to go.

There's nothing particularly challenging about making your own pho, you just need to give the beef broth the love it deserves, which means taking your time and not cutting corners. Doing so "[makes] the difference between a pho that sings and one that just sits there," according to Tanis.

So there aren't really any tricks, but there are a few secrets, things that might not be obvious when you taste the finished product, but give a true pho bo its depth. Like using leg bones in your broth to get an extra-rich flavor.**** And lightly charring an onion and some ginger root at the outset. And getting the mix of spices just right.***** And fish sauce--don't forget the fish sauce.

Tanis isn't particularly prescriptive--he encourages his readers to become "pho fanatics" (pho-natics?), if they aren't already, and develop their own "house pho"--but he offers a very handy blueprint, one that's quite a bit more subtle than Nguyen's version (fewer bones, less star anise), but one that's got all the grace of a true homemade pho.

fig. d: spring rolls

fig. d: spring rollsWe took our time, followed all the steps in Tanis's recipe, made some spring rolls to tide us over, and relaxed. Three hours later, our big bowls of steaming homemade pho bo before us, we dug in and let that magical Vietnamese elixir do its work.

figs. e & f: straight-up & all-dressed

figs. e & f: straight-up & all-dressedPho Bo

the soup:

1 1/2 lbs short ribs

1 1/2 lbs oxtails or beef shank

1 large onion, halved

1 3-inch piece unpeeled ginger, thickly sliced

6 quarts water

1 star anise

1 small piece cinnamon stick

1/2 tsp coriander seeds

1/2 tsp fennel seeds

1/4 tsp whole cloves

6 cardamom pods

2 tbsp soy sauce

1 tbsp fish sauce

2 tsp sugar

salt and pepper

1 lb dried rice noodles

1/2 lb fresh bean sprouts

1 sweet red onion, thinly sliced

fig. g: garnishes

fig. g: garnishesthe garnishes:

mint sprigs

cilantro sprigs

basil sprigs

6 scallions, slivered

2 serrano or 6 small Asian chiles, finely slivered

lime wedges

Bring a large pot of water to a boil. Add the short ribs and oxtails and boil for 10 minutes, then drain, rinse the meat, and discard the water. This step rids the meat and bones of impurities and results in a cleaner-tasting broth. It's a step that's common in many Asian cuisines, including Chinese.

Set a large heavy-bottomed soup pot over medium-high heat, add the onion, cut side down, and ginger, and lightly char for about 10 minutes, until the halves are charred but not quite burnt. Add the short ribs, oxtails, and the 6 quarts of water and bring to a hard boil, then turn down to a simmer. Add the spices. Then add the soy sauce, fish sauce, sugar, and salt and pepper and let simmer, uncovered. Skim off any rising foam, fat, and debris from time to time.

Check the tenderness of the meat after about an hour. It will probably take an hour and a half for the meat to get really fork-tender, but it's better to be safe than sorry.

When the meat is done, remove it from the pot, take the meat off the bones, and reserve. Put the bones bak in the pot to simmer in the broth for another hour and a half.

When the broth is done, taste it for salt and add more if necessary. Strain it through a fine-mesh strainer. Chop the cooked meat and add it to the broth. At this point, you can either cool and refrigerate the broth for later use, or proceed.

When you're ready to serve the pho, put the rice noodles in a large bowl and pour boiling water over them. Let them sit for about 15 minutes (possibly longer) to soften, then drain.

Heat the soup until it's piping hot. Prepare a large platter of the garnishes. We're especially fond of mint, cilantro, scallions, and lime wedges, but here's your opportunity to customize.

Line up the soup bowls (Tanis recommends "deep, giant Chinatown-style bowls"). Put a handful of noodles in each soup bowl and scatter some bean sprouts on top. Add a few raw onion slices. Ladle the broth and a bit of boiled meat into each bowl. Pass the platter of garnishes and let everyone add their own herbs, scallions, chiles, squeezes of lime, etc., as they see fit.

Oh, yeah: and don't forget the Sriracha.

Serves 4 to 6 generously.

[based very, very closely on David Tanis's "Pho (Vietnamese Beef Soup)" recipe in Heart of the Artichoke]

That pho--and the whole process that went into it--really left an impression on us. So much so, that a few days later, back in Montreal, Michelle and I made it again. The whole thing. Start to finish.

fig. h: photo #3

fig. h: photo #3And it was just good as ever. Basic, hearty, and filling, and available in our very own kitchen. Not street food, not diner food, but true homemade comfort food.

aj

* For a truly magnificent account of the ins and outs of eating in Vietnam, check out "Saigon Seductions" @ The Traveler's Lunchbox.

** The Vietnamese food explosion of the last 35 years has been nothing if not phenomenal.

*** If pho hits the spot on "one of those damp, chill spring days in Paris," imagine just how soothing it must be on a bone-cold winter day in Upstate.

**** Meat + bones + marrow = extra-rich flavor.

***** You're basically replicating the contents of this bag,

fig. i: "chinese special spice"

fig. i: "chinese special spice"but with fresher, better-quality spices (hopefully). We highly recommend getting your fennel, in particular, from our good friends the De Viennes at Épices de Cru.

p.s. Extra-special thanks to S & T (and V too).