fig. a: M. Bertrand’s garlic

fig. a: M. Bertrand’s garlic

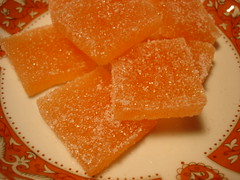

Sometime in August, Michelle picked up Richard Olney's A Provençal Table: The Exuberant Food and Wine from the Domaine Tempier Vineyard for the first time in a while. There was something in the air at the time (Was it the weather? The figs at the market? The garlic we’d seen at M. Bertrand’s [pictured above]? Who knows?) that had her daydreaming about Provence, and the next thing I knew she was toting Olney's classic from one to room to the next, reading bits and pieces as she went. Gradually the book started to fill up with the little colored Post-It® flags and before long I could tell she was planning a menu. Sure enough, a few days later Michelle began to reveal to me the finer points of the Grand Aïoli.

Richard Olney, the ex-pat American artist, gourmet, and food writer, got to know the Peyraud family, whose kitchen was the inspiration behind and the source of "the exuberant food and wine" he detailed in A Provençal Table, in the 1960s sometime after he bought an abandoned property near the tiny town of Solliès-Toucas, just a few kilometers to the northeast of Toulon. Olney continued to split his time between Provence and Paris for a few years, but after the construction of the fireplace that became the centerpiece of Olney's very own Provençal kitchen in 1964, Olney began to live in the south nearly year-round, where he'd become thoroughly enchanted by "the light, the landscape, and the odors of Provence." The Peyrauds--Lucien and Lulu, and their five children--lived on the grounds of Domaine Tempier, just outside of Bandol, a few kilometers to the west of Toulon. There they ran the Domaine Tempier vineyard, which they'd turned into an important part of the renaissance in Bandol-region winemaking, a renaissance that resulted in an AOC designation in 1941 followed by international acclaim from the likes of Kermit Lynch and Robert Parker. More importantly, they'd turned Domaine Tempier into what Olney considered a perfect expression of all that was wonderful and true about Provence.

Domaine Tempier is also the Peyraud family, impassioned, exuberant, indefatigable, dedicated to the belief that the meaning of life lies in love and friendship and that these qualities are best expressed at the table. Perhaps love and friendship can never be quite the same in the absence of the cicada's chant, of fresh sweet garlic and voluptuous olive oil, of summer-ripe tomatoes and the dense, spicy, wild fruit of the wines of Domaine Tempier, which reflect the scents of the Provençal hillsides and joyously embrace Lulu's high-spirited cuisine. For Lulu, cuisine is a language, the expression of love; for Lucien, wine is the expression of love. In Provence, cuisine and wine are as inseparable as Lulu and Lucien.

If Richard Olney was the godfather of Chez Panisse and, by extension, an entire strain of California Cuisine, Lulu could be considered the godmother. Olney made sure to introduce the young Alice Waters to the Peyrauds when she came to visit sometime in the mid-1970s. Waters later described the experience as being akin to "[walking] into a Marcel Pagnol film come to life," and Domaine Tempier would have a huge influence on Chez Panisse's approach to cuisine. By 1976, when Lucien and Lulu came to the San Francisco Bay Area as representatives of the Office International de Vigne et du Vin, Alice Waters and the rest of the Chez Panisse team were already eager to repay the Peyrauds for the invaluable lessons they'd imparted. As Lulu later recalled, "In 1976, we went all alone, like real grown-ups, to California, where we ate crabs on the San Francisco waterfront like everyone else--but then we had dinner at Chez Panisse... and that was not like everyone else!... a leg of lamb and a tart that I will remember all my life long!"

One of the meals that best summed up Lulu's approach to cuisine and to entertaining was the

Grand Aïoli. A traditional Provençal feast meant to celebrate the harvest, in the hands of the Peyrauds' the

Grand Aïoli became "a mad, joyous circus," one that appears to have left a deep impression on Olney. The

Grand Aïoli was "an abundant meal, a traditional cornucopia of products of the earth and the sea, accompanied," as the name suggests, "by an aïoli sauce," but it also captured Provençal cuisine at its most communal. Michelle was absolutely taken in by Olney's descriptions of the

Grand Aïoli, and she had visions of setting a grand table of her own in Grandma and Grandpa's garden down below and presiding over a feast worthy of Domaine Tempier, of becoming Lulu herself, if only for a day. She imagined our neighbors' prying eyes looking down from their balconies wondering what on earth the occasion could be, mesmerized by the lovely aromas, the boisterous conversation, and the Continental flair of the spectacle below. What she got was something altogether different: a rainy day that kept us in the confines our big, bright, but not particularly Provençal apartment, and an abject lesson in how difficult it is to pull off "a Lulu."* The

Grand Aïoli was a big success, it's just that we didn't exactly manage to "make it look easy."

One thing you'll notice as you read through the recipes below is the preponderance of two ingredients. The first is garlic, of course. It wouldn't be aïoli without lots of garlic; it wouldn't be a

Grand Aïoli without a whole lot more. The second is salt-packed anchovies.

fig. b: Italian salt-packed anchovies

fig. b: Italian salt-packed anchovies

Salt-packed anchovies aren't exactly easy to find here in Montreal--in all likelihood you're going to need to make a trip to Little Italy in order to score your own tin--but they're worth the effort and they're absolutely essential to the recipes we've included. You'll find the flavor to be entirely different in nature--heartier, deeper--than the anchovies you're used to, and they also have a very different texture than their oil-packed cousins. Both of these ingredients are quintessentially Provençal--bold and unmistakable--and consequently the

Grand Aïoli is not a meal for the faint of heart. It's a sophisticated meal with many nuances to it, but let's not kid ourselves, the flavors are strong and evidently not to everyone's tastes.

I say "evidently" because that very same weekend

The Montreal Gazette ran a profile of a local fine foods merchant and tastemaker who declared outright his contempt for garlic, explaining that he preferred the more subtle flavors of garlic

shoots. We were in shock, and, given the meal we'd planned for the next day, that interview provided us with no shortage of amusement. I mean, we've certainly met non-garlic eaters in our time (whether for cultural reasons, or just because they were unusually obsessed with upkeeping fresh breath), but coming from a

professional gourmet?! Around here, we tend to be suspicious of those who shun garlic. You might as well tell us that you recoil at the sight of a cross, that you've been having recurring nightmares involving silver stakes, or that you fear the light of day. I mean, we're the kind of people that the garlic vendors at Jean-Talon sell their

grand cru garlic to, because they're sure that we won't let it sit around and lose its potency (i.e. we'll go through a braid in 2-4 weeks). Now, this isn't to say that we were harboring fears about any of the guests we'd invited over for our

Grand Aïoli, but I'm happy to say that every last one of them passed the test. This was no small feat either. We hadn't held back in the least. Olney recounts how Lulu was known to make two batches of

aïoli. One for the Parisians, Americans, and other non-believers, and one “overpowering” batch for her beloved Lucien and all those Provençaux worth their salt. Our batch was definitely Lucienesque.

In the end, this was the menu that Michelle devised (price of admission: one good bottle of French wine, preferably Provençal; absolutely no "Chateau Dep"):

pissaladière

tapenade

Bohèmienne

olives

bread

Grand Aïoli

salad

dessert

And here are all the recipes you need for your very own

Grand Aïoli, keeping in mind that we provided a perfectly excellent recipe for a

pissaladière back in

June of 2005.

Tapenade

1/2 lb large Greek-style black olives, pitted

2 salt anchovies, rinsed and filleted

3 tablespoons capers

1 garlic clove, peeled and pounded into a paste in a mortar with a pinch of coarse salt

1 small pinch of cayenne

1 tsp young savory leaves, finely chopped, or a pinch of crumbled dried savory leaves

4 tbsp olive oil

Reduce the olives, anchovies, capers, garlic, cayenne, and savory to a coarse purée in a food processor. Add the olive oil and process only until the mixture is homogenous--this should only take a couple of rapid whirs of the food processor.

Bohèmienne

6 tbsp olive oil

1 large onion, halved and thinly sliced

3 garlic cloves, crushed and peeled

2 lbs eggplant, peeled, sliced into rounds, salted on both sides for 30 minutes, and pressed between paper towels until dry

2 pounds tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and coarsely chopped

3 salt anchovies

salt and pepper

In a heavy sauté pan, warm 4 tbsp olive oil over low heat. Add the onion and cook, stirring regularly with a wooden spoon until softened but not colored. Add the garlic and eggplant. Cook until softened, stirring regularly. Add the tomatoes, turn up the heat, and stir until they begin to disintegrate and the mixture begins to boil. Lower the heat to maintain a simmer, uncovered, for an hour or more. Stir regularly, crushing the contents with the wooden spoon and, after about 45 minutes, crush regularly with a fork to create a coarse purée from which all the liquid has evaporated. Toward the end, it should be stirred almost constantly to prevent sticking and the heat should be progressively lowered.

Pour 2 tbsp olive oil into a small pan, lay out the anchovy fillets in the bottom, and hold over very low heat until they begin to disintegrate when touched or when the pan is shaken. Removed the eggplant-tomato purée from the heat and stir in the anchovies and their oil. Taste for salt and add some freshly ground black pepper to taste. If prepared in advance, transfer the Bohémienne to a bowl and leave, uncovered, to cool completely before covering and refrigerating.

Lulu’s Grand Aïoli

1 recipe Aïoli

2 lbs salt cod, soaked and poached

1 pound green beans, parboiled (about 5-8 minutes) in salt water

16 small carrots, peeled and parboiled (12-15 minutes) in salt water

8 small new potatoes, parboiled (about 20 minutes) in salt water

1 cauliflower, broken into florets and parboiled (3-4 minutes) in salt water

8 young artichokes, parboiled (about 20-30 minutes) in salt water, split in two, and chokes removed

4 medium beets, peeled and quartered and baked at 375º F for about 45 minutes

8 sweet potatoes, chopped and baked at 375º F for about 45 minutes

8 firm ripe tomatoes, peeled

1 recipe Stewed Octopus

Grand Aïoli à la "...an endless banquet"

1 recipe Aïoli

1 pound mixed green and yellow beans, parboiled (about 5-8 minutes) in salt water

16 mixed small yellow, red, and orange carrots, peeled and parboiled (12-15 minutes) in salt water

8 small new potatoes, washed, dried, and baked at 375º F for about 45 minutes

1 cauliflower, broken into florets and parboiled (3-4 minutes) in salt water

8 young artichokes, parboiled (about 20-30 minutes) in salt water, split in two, and chokes removed

4 mixed medium red and yellow beets, peeled and quartered and baked at 375º F for about 45 minutes

8 baby white turnips, washed, trimmed and quartered and baked at 375º F for about 45 minutes

8 firm ripe tomatoes, sliced

1 recipe Stewed Squid

Aïoli

1 large pinch of coarse sea salt

1 head (more or less to taste) garlic, cloves separated, crushed, and peeled

2 egg yolks, at room temperature

2 cups olive oil, at room temperature

1 to 2 tsp water, at room temperature

In a marble mortar with a wooden pestle, pound the salt and garlic into a smooth paste. Add the egg yolks and stir briskly with the pestle until they lighten in color. Begin to add the oil in a tiny trickle, to the side of the mortar so that the oil flows gradually into the yolk and garlic mixture, while turning constantly with the pestle. As the mixture begins to thicken, the flow of oil can be increased to a thick thread, always to the side of the mortar. Never stop turning this pestle using a rapid beating motion. When the aïoli is quite thick, add a teaspoon or tow of water to loosen it, while turning, and continue adding oil until you have obtained the desired quantity and consistency. Cover and refrigerate until serving.

(Makes about 2 cups.)

Stewed Squid

5 tbsp olive oil

1 large sweet onion, finely chopped

4 garlic cloves, crushed and peeled

2 tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and coarsely chopped

salt

3 lbs squid, cleaned, rinsed, and chopped into bite-size pieces

1 bay leaf

4 tbsp marc de Provence or Cognac

1/2 cup acidic white wine

In a large frying pan, warm 3 tbsp olive oil, add the onion and garlic, and cook over low heat, stirring with a wooden spoon, until soft and golden but not browned. Turn up the heat, add the tomatoes and salt, and sauté, tossing regularly, until the tomato liquid has evaporated.

At the same time, in a large earthenware poêlon or heavy sauté pan, heat 2 tbsp olive oil, add the squid, salt, and bay leaf, stir with a wooden spoon, and shake the pan regularly until any liquid thrown off by the squid has come to a full boil. Add the brandy, ignite it, and stir until the flames die. Bring the white wine to a boil in a small saucepan and add it. Boil for a few minutes, stirring, to partially reduce it and ride the wine of its alcohol and stir in the sautéed onion, garlic, and tomatoes. Bring back to a boil and adjust the heat to maintain a gentle simmer, uncovered, stirring regularly, for about 40 minutes, or until the squid is tender. If preparing the stew ahead, leave to cool uncovered and reheat over very low heat, stirring all the while. If prepared the previous day, cool uncovered and refrigerate covered before reheating, uncovered.

[If you'd like to make the Stewed Octopus instead (of which Olney writes: "The star preparation of Lulu's Grand Aïoli is the stewed octopus, a dish that arouses passions, not only in the Peyraud family but in all who have tasted it--when the octopus sauce and aïoli meet, flavors explode."), the instructions are the same. Just make sure to freeze the octopus first, which will help tenderize it, and simmer the octopus for an additional 10 minutes, about 50 minutes in total.]

Be sure to start early when preparing your very own

Grand Aïoli, you'll find it much more relaxing and I'm sure that's the way Lulu would have liked it. One thing that we did to cut down on the number of steps involved was to roast more of the vegetables than Olney and the Peyrauds recommend. This meant that we had a lot less parboiling to do and that we could just throw a large casserole in the oven for 45 minutes and take care of several vegetables in one fell swoop. Add some olive oil and some coarse sea salt to your casserole and you're golden (as will be your vegetables). We absolutely loved the tapenade

à la Lulu, the

Bohèmienne, which was one of the best eggplant dishes either of us had ever tasted, and the Stewed Squid with its rich flavor and its flambéd overtones, but the roasted beets dipped in that fearsome

aïoli might have stolen the show.

aj

*An act sometimes known around here as "a real Lulu."

fig. a: tending the garden

fig. a: tending the garden fig. b: "fireplace at Solliès"

fig. b: "fireplace at Solliès" fig. c: the good cook does wine

fig. c: the good cook does wine fig. d: desperate measures

fig. d: desperate measures