fig. a: flaky pilot

fig. a: flaky pilot

I’ve said it before, but there’s something about those dishes that spark controversy, the ones that people worked up about, the ones that they’ll argue over late into the night. They’re the ones that have the greatest relevance to the greatest cross-section of people, the ones that are at the very heart of a culture, and that serve to define it. In other words, the level of controversy is an indicator of cultural significance. Of course, in the hyper-opinionated world we live in, with its discussion groups, chat rooms, comments sections, "likes" functions, etc., it's sometimes hard to distinguish a true controversy from your standard-issue tempest in a teapot. But there's a reason that people get so agitated about things like barbecue, chili, and pizza. Stakes is high.

Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but I get the feeling that that moment has passed when it comes to chowder, that chowder is no longer as absolutely central to the culture and the identity of vast numbers of North Americans, especially those hailing from the Mid-Atlantic and points north and east, as it was just a few decades ago. Blame it on America’s continued drift westward and southward, blame it on decades of relentless attacks against New England and its notorious liberal elites, but take a look back and you’ll see that chowder was as hotly contested and divisive a dish as there was in North America. Sure there was that fabled Boston vs. Manhattan split, but, really, it went way, way beyond that. So far, in fact, that when J. George Frederick waxed enthusiastic on the topic of chowder for his Long Island Seafood Cook Book of 1939 (reprinted in a Dover edition in 1971), not only did his chapter span 38 pages and roughly 60 recipes covering seafood chowders of all sorts (clam, fish, oyster, and shrimp included), as well as a host of other related soups and stews (from the prosaic [Fishwife’s Stew] to the exotic [Sea Tang]), but the magnitude of the topic elicited a particularly memorable title from him: “The Great Disputatious Chowder Family.”

Mr. Frederick explained:

If anybody tells you that the American people are “regimented” or “standardized,” just ask quietly, “What about clam chowder?” Your cocksure informer will get very red in the face, for nothing is more notorious that that various sections of Eastern America come to blows over chowder. Tomatoes or milk is the crucial question, also caraway seeds and salt pork. New England is rent and torn over these dissenting practices, but Boston, Maine, and Connecticut are allied against Manhattan or Long Island chowders, while Rhode Island teeters in between.

As Mr. Frederick would have it, and as has become accepted knowledge since, chowder, that most Yankee of dishes, has its roots in Brittany’s tradition of

faire la chaudière, where the citizenry of coastal towns would each contribute something to the communal pot, be it fish, vegetable, or spices and herbs, and each would partake of the dish that resulted, a “hodgepodge” (Frederick’s term) consisting of “

fish and ship biscuits, vegetables and savory ingredients” (my emphasis).

When French fisherman began settling in Newfoundland to take advantage of the (then) teeming bounty of the Grand Banks, they naturally brought

faire la chaudière with them, transplanting it to the New World, where the tradition quickly took root. There it became part of the cultural exchanges (French, British, Portuguese, Spanish, etc.) that defined coastal Newfoundland, and eventually found its way southwest, through the Maritimes to New England, with the assistance of the sailors and fishermen who had made seafood chowder their own, and whose travels often covered vast areas of the Atlantic Seaboard.

Though this was not a part of the original French tradition, Early American chowders were predominantly milk-based chowders--when they became so is unclear. Was this an American invention? Did it have roots in such time-honored Northern European concoctions as Flemish

waterzooi? I’m not sure. What is clear is that even though the tomato originated in the Americas, the addition of tomato to American chowder came relatively late in the game, and, most likely, it came by way of Europe. During its early history, authentic American chowder was based on this fab four and this fab four only: seafood, potatoes, pork (usually salt pork), and hardtack/sea biscuit, or some analog, such as pilot biscuits (preferably flaky ones) or common crackers.

fig. b: flaky pilot biscuits

fig. b: flaky pilot biscuits

The tomato was a late arrival to the world of chowder, but when it did, its effect rippled out from the New York area where it first came into vogue, throughout the Mid-Atlantic

and New England. Some 70 years ago, at the time that Mr. Frederick published his tome, Long Island was a divided island, but his account took pains to indicate the complexity of the matter:

Since Long Island has all this time been the place where New York and New England merge (at the eastern tip) it is not surprising that the chowder controversy rages even today on Long Island, despite the fact that a majority opinion certainly sides with the tomato. But a few old, gnarled eastern island baymen, and hardy old ladies, who learned the cookery arts somewhere around the Civil War period when the tomato was still an outlaw, today continue to cling to the milk basis for chowder, and will not surrender. Canceling this out is the fact that many New Englanders, even up into Maine, and particularly in Rhode Island, have acquired the tomato chowder idea and uphold it against their scandalized neighbors. Connecticut is too close to New York to be pure New England, and also is in part a renegade from the milk chowder. And, in the main, west of the Hudson, as New York goes, so goes the U.S.

If anything, I’d argue that “Boston” or “New England-style” chowder has been the style that's dominated the continent in recent decades, but there’s no question that each tradition has had tremendous reach. Back in the day, my family’s favorite chowder house in Santa Cruz, CA, was just one of many such establishments that handled any possible disputations with the greatest of tact (or was it spinelessness?): they served both.

In any case, for my money, the tomato vs. milk debate is a bit of a non-issue. Properly made, I’d be happy (ecstatic, even) with either. The real issue for me in recent years has been finding a chowder made from scratch, one made from fresh seafood and not from its canned or frozen doppelgänger, and one made without the use of corn starch and other non-traditional thickening agents. The idea is to use the freshest possible seafood (recall the concept behind

faire la chaudière), and to achieve thickness from the inclusion of the hardtack/sea biscuit/pilot biscuits/common crackers and, especially, the potatoes. In fact, the traditional Yankee seafood chowder was known to begin with potatoes cut in irregular shapes, one end purposely cut larger than the other. This facilitated one end cooking faster than the other, disintegrating into the broth, and lending the chowder a perfectly thick texture without the need of any additional agents. Few things disappoint me as much as a corn-starch-laden seafood chowder, especially when served at an

otherwise reputable establishment; few things are as totally satisfying as a

true seafood chowder.

The following is the recipe we’ve been using recently for our New England-style fish chowder. It's an amalgam of a few different recipes. If, however, your preferences are tomato-based and spicy, you might want to check out this

recipe, which appeared in “...an endless banquet” way back in 2004. It's a great recipe for Manhattan clam chowder, and it might also give you ideas for a spicy fish chowder.

fig. c: fish chowder

fig. c: fish chowder

AEB Fish Chowder

1 lb haddock, or cod, fillets

1 bay leaf

1/4 lb bacon ends, or bacon, or salt pork (salt pork being the most traditional option; smoky bacon ends being what we've actually been using of late)

1 medium onion, finely chopped

1 small leek, white part only, thoroughly rinsed, cleaned, and finely chopped

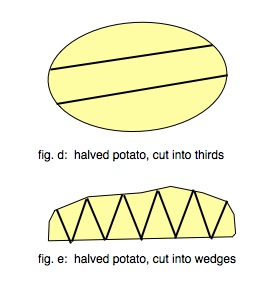

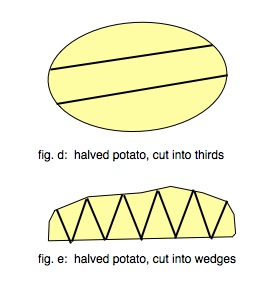

2-3 medium potatoes, chopped into irregular pieces as described above and pictured below (see figs. d & e)

1 tbsp parsley, minced

2-3 sprigs thyme, leaves only, minced

1 1/2 cups milk

salt and freshly ground black pepper

pilot biscuits or common crackers

Bring three cups of lightly salted water to a boil. Add the fish and the bay leaf, lower the heat, and simmer gently for 7-8 minutes. Using a slotted spoon, remove the fish to a plate or cutting board, but keep the broth warm on a back burner. Fry the bacon ends (or bacon, or salt pork) in a skillet until they've rendered their fat and have begun to crisp. Add the onion and the leek and sauté until the onion begins to turn translucent and the leek has turned tender. Add the onion/leek mixture and the chopped potatoes to the fish broth. Bring to a boil, lower the heat, and simmer for 12-15 minutes, until the potatoes are nice and tender and the broth has thickened slightly. Meanwhile, gently flake the fish fillets. When the potatoes are ready, turn the heat down to the lowest setting, add the fish, the parsley, the thyme, and the milk to the broth, and let the chowder steep for 5-10 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasoning.

Set your oven to broil. Split your common crackers or pilot biscuits, and if you're using the latter, break them up into smaller pieces. Being careful not to over-toast them (read: burn them), toast your common crackers or pilot biscuits gently, until they're a light golden brown. (Sounds unnecessary, but it will only take a minute and, trust me, toasting them makes a huge difference.)

Serve each bowl of chowder topped with the toasted pilot biscuits or common crackers.

Serves 4.

Note: fish chowder tastes good at any time of year, but it's particularly good on a cold winter day.

fig. f: cold winter day

fig. f: cold winter day

aj

fig. a: reunited, and it feels so good*

fig. a: reunited, and it feels so good*