fava up first

fig. a: the three faces of fava

fig. a: the three faces of fava

As Alice Waters puts it in Chez Panisse Vegetables, "The fava bean, Vicia fabia, was the bean of Europe before contact with the New World." A few hundred years later, the fava bean--especially in its young, tender, spring/summer incarnation--became the bean of California Cuisine. Waters goes on to describe the scene at Chez Panisse every spring when the favas come into season:

Shelling fava beans has become a springtime ritual at the restaurant. Big baskets of them are brought out to keep all hands busy during long meetings, menu discussions, and even job interviews.

And in the Chez Panisse Café Cookbook, Waters puts it like this:

It's not uncommon in informal cafés in Europe to see waiters peeling garlic during a quiet time. At Chez Panisse, they peel fava beans--lots of them. Sometimes the customers standing at the bar help out.

Here in Montreal, fava beans are hardly an important part of the local cuisine--nouvelle or otherwise--but there is certainly enough of a Mediterranean presence in the region (thank god!) to make fava beans a part of our seasonal, early-21st century diet. You definitely have to go out and look for them, though--in your markets, in your seasonally minded restaurants. And, remember, the season is short. As indicated above, fava beans are very much a harbinger of spring in Northern California. Around here, however, they're a mid-summer crop, and, friends, the time is now.

To get the full fava bean experience, you have to do a little work--shelling and peeling them requires some determination because you have to get from that big, long, fleshy pod stage, to that pale green/off-white stage, to that bright green stage [pictured above]--but all that work pays off, because once you've managed to extract that bright green, kidney-shaped bean from its protective layers, the cooking time is practically instant, and its seductive charms are immediate.

Most standard accounts of shelling and peeling favas go something like this one in Alice Waters, Patricia Curtan, and Martine Labro's Chez Panisse: Pasta, Pizza, and Calzone:

Picked young enough, they can be shelled and eaten raw, skin and all. When they are a little older and the skin is no longer bright green, they must be skinned. A good way to do this is to blanch the shelled beans for a minute or so [elsewhere Waters recommends "30 seconds to 1 minute"] in boiling water. Drain them and allow to cool. Use your thumbnail to pull open the sprout end and squeeze the bean out of its skin. It will pop right out. Once you get the hang of it, this goes very quickly.

Some chefs, like Zuni Cafe's Judy Rodgers, prefer keeping fava beans raw, arguing that the blanching process, however short, changes the texture of the beans too much. But in our own experience, blanching the beans for 30-60 seconds has produced the results we've been the happiest with. If you want to give raw fava beans a spin--and there's no reason you shouldn't--both Rodgers and Waters recommend serving them in the Tuscan style, with salami, and possibly a sheep's milk cheese (Rodgers also recommends a Ligurian white--Vermentino "Vigna U Munte," Colle dei Bardellini, 2000--as her wine pairing).

But, like I said, our favorite fava bean preparation involves blanching the beans slightly, then gently sautéing them to create a basic ragù. The last fava bean dish I made was based on this recipe from Waters, Curtan, and Labro's book:

Fettucine, fava beans, saffron, & crème fraîche

1/2 pound [fresh] fava beans

1 tbsp virgin olive oil

1 clove garlic

salt and pepper

a few fresh basil leaves

3/4 cup crème fraîche

saffron

fettucine for 2

fresh chives

Shell and skin the fava beans [see directions above]. Cook them gently in olive oil with the chopped garlic for 2 to 3 minutes. Season with salt and pepper. Add some basil leaves cut in ribbons, the crème fraîche, and a small pinch of saffron. Cook another few minutes, then cook the fettucine and add to the beans. Season the noodles with salt and pepper and toss with the favas. Serve garnished with a sprinkling of chives.

I liked the idea of combining sautéed fava beans with saffron, but I also wanted to combine them with ricotta salata, an idea I'd swiped from yet another recipe. Our fava bean and pasta recipe went something like this.

Fava beans & farfalle

1 pound fresh fava beans

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

saffron

3 cloves garlic, finely minced

zest from one lemon, finely minced

4 spring onions, chopped

1 lb farfalle

1/2 cup grated ricotta salata

salt and pepper

basil leaves

Shell and skin the fava beans [see directions above]. Heat the olive oil in a frying pan over medium heat. Add the saffron, stir briefly so that the olive oil begins taking on the saffron's color, then add the fava beans. Sauté the beans for 30-60 seconds, then add the garlic and the lemon zest and sauté for another few minutes, until the garlic becomes lightly golden. Turn off the heat and add the spring onions, folding them into the mixture.

Meanwhile cook the farfalle until al dente. Drain the pasta, reserving about a cup of the pasta water.

In a large bowl, mix together the pasta, the fava bean mixture, and the ricotta salata, adding a bit of the pasta water if the combination seems dry [note: you may not need to add any additional liquid]. Salt and pepper to taste, keeping in mind that the ricotta salata is very salty (hence the name), so make sure to taste the pasta before adding any salt, because you might not need any.

Have fun. Act fast. Eat well.

Good sources for fava bean recipes:

Judy Rodgers, The Zuni Cafe Cookbook

Alice Waters, Chez Panisse Vegetables

Alice Waters, Chez Panisse Café Cookbook

Alice Waters, Patricia Curtan, and Martine Labro, Chez Panisse: Pasta, Pizza, and Calzone

Paula Wolfert, Paula Wolfert's World of Food

Great source for fava beans:

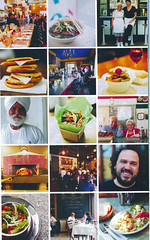

Birri & frères, Jean-Talon Market, 276-3202

aj