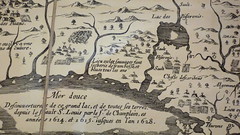

fig. a: The Fruit Hunters

fig. a: The Fruit Hunters

Only one week in print and already Adam Leith Gollner's The Fruit Hunters: A Story of Nature, Obsession, Commerce, and Adventure (Doubleday Canada, Scribner) has gotten itself embroiled in a full-blown tale of, well, nature, obsession, commerce, and adventure. Yes, The Fruit Hunters has been receiving all kinds of accolades from the likes of The Montreal Gazette, The Toronto Star, The National Post, and The New York Times since its release, but over the weekend Mr. Gollner and his book helped generate a craze the likes of which the fruit world has not seen since Kiwimania. Within hours, not only had a New York Times story on miracle fruit (one of The Fruit Hunters' featured fruits) shot to the top of their "most emailed" list, but the Miracle Fruit Man, North America's best (only?) source of miracle fruit, was totally sold out of these little red taste-enhancers.

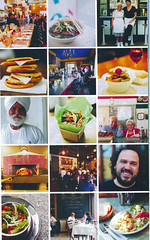

fig. b: From New France (a.k.a. "[le] lieu ou les sauvages font secherie de framboise, et blues tous les ans"*)...

fig. b: From New France (a.k.a. "[le] lieu ou les sauvages font secherie de framboise, et blues tous les ans"*)...

fig. c: ...to Brazil

fig. c: ...to Brazil

But there's more to The Fruit Hunters than mere hype. Much more. Mr. Gollner's book is encyclopedic in its scope (Borneo to Budapest, coco-de-mer to Calville Blanc d'Hiver, fruitarians to fruit detectives, Ah Bing to St. Hildegard von Bingen), and utterly devoted to giving the wide world of fruit--and the bizarre characters who populate it--its due. It also happens to be a rollicking ride that's nearly impossible to put down.

Regular readers of "...an endless banquet" might recognize Mr. Gollner as a long-time associate and recurring character in our own ongoing tales of adventure, where he's carried the monikers "A.," "Adam," and "the Fruit Guru." We thought it might be nice to do an interview with him in anticipation of the official Montreal launch of The Fruit Hunters (details below), and he was kind enough to take the time from his whirlwind book tour to answer some of our questions.

AEB: A noted gourmand** once wrote an essay entitled simply “Food.” The first section bore the heading “Fresh Figs” and it began like this: “No one who has never eaten a food to excess has ever really experienced it, or fully exposed himself to it. Unless you do this, you at best enjoy it, but never come to lust after it, or make the acquaintance of that diversion from the straight and narrow road of the appetite which leads to the primeval forest of greed. For in gluttony two things coincide: the boundlessness of desire and the uniformity of the food that sates it. Gourmandizing means above all else to devour one thing to the last crumb. There is no doubt that it enters more deeply into what you eat than mere enjoyment.”

Reading The Fruit Hunters, it seems pretty clear that the pursuit of fruit eventually led you to that primeval forest. If so, when did you get there, and what was the fruit involved?

AG: That quote has an almost alchemical quality. It transmutes the base sinfulness of gluttony into a golden promise of hope, the hope that your greed is somehow aligned with God’s inner wishes for humankind’s happiness. It almost absolves the gluttons amongst us of our boundless desires. Nature is infinite in its diversity, it seems to suggest; shouldn’t all our banquets therefore be endless?

The forest – from the latin foris, meaning outside – has always been a place for outsiders. I have long been fascinated with all things sylvan (not entirely excluding Sylvain Sylvain LPs, although as I type this I grow momentarily wistful; it is as though I can just make out the soft contours of a grove near my childhood home, its swamps rippling with reeds and tadpoles, its trees teeming, I was convinced, with gorillas).

But let’s stick to the figs. This “noted gourmand,” with her (his?) essay on fresh figs, reminds me of the self-professed “fignatics” in The Fruit Hunters. Perhaps it’s true: if you’ve never eaten a food to excess maybe you’ve never really experienced it, never attained that transcendental merging of hunter and hunted. This argument helps dissipate the guilt swirling around some of my own more indulgent fruit experiences. The author might argue that I wouldn’t have been able to understand the lure of fruits without overdosing on them. A seductive notion. Nevertheless, I still recall the moment of moments where I hit my nadir – or was it my zenith? It matters not; that moonlit revel in the treetops of my own primeval greed forest took place on a trip to Borneo.

I was staying in the hotel Telang Usan, which is run by members of the Orang Ulu tribes. I’d been gifted a chempedak, an army-green, rugby-ball-sized fruit filled with honey-sweet orange chunklets of syrupy deliciousness [to even begin to understand the alien splendour of the chempedak you have to see it to believe it--ed.]. Chempedaks, I wasn’t yet aware, also happen to give off a putrid stench that befouls any enclosed space. It does this as a way of luring apes and jungle cats in the hopes of being eaten and thereby having its seeds dispersed.

That afternoon, I’d taken a couple of tentative bites. Unimpressed, I left the fruit on the nightstand of my third story hotel room, alongside a bunch of other weird fruits I had no idea how to eat. Some of them resembled pink cupcakes covered in op-art swirls; one other unwieldy aberration looked just like a punching bag when I discovered it hanging off a tree.

I’d been spending my days going to all sorts of obscure fruit markets in pursuit of a pitabu that I’d heard tastes like orange sherbet and raspberries. Unfortunately, it wasn’t in season. As a result, I was making feverish plans to come back to Borneo. Poring over guides to the fruits of Sarawak, I was making lists of all these obscure fruits I just NEEDED to experience. I distinctly recall photographs of tampois with pearly, transluscent interiors that made me almost tremble with desire. My guides from the Malaysian department of agriculture insisted that I’d need to come back at least three or four more times in order to taste them. Even then, there’d still be some fruits I wouldn’t be able to get to. The world’s greatest authority on the region’s fruits, Voon Boon Hoe, hadn’t even tasted them all, and he’d lived in Borneo all his life.

After dinner at the hawker stand nearby, I came back into my hotel in an obsessed stupor, dizzy from the tentative scheduling and list-making. As soon as I walked into the lobby, my nostrils were smacked with a penetrating funk of sulfurous decay. My chempedak! Its gaseous third-floor emanations had overrun the Telang Usan. The gentle tribespeople on night-duty at the reception area didn’t seem to mind (in fact, one of the hotel employees – a descendent of the Iban, also known as the Sea Dyaks, a once-ferocious tribe that practiced head-hunting – ended up taking me to eat langsats near her grandma’s longhouse, which had the motto “We believe in infinity.”)

I was mortified about my fruit-bomb, and quickly smuggled it out of the room. Escaping through a rear entrance, I sat down in a vacant lot covered in stray greenery and started pulling the fruit’s sections apart. The smell was actually quite pleasant here in the open air. I will now enter the present tense and quote from The Fruit Hunters:

“Crouching under a streetlight as the moon wavers in the thick haze, I dig in. Its flavor has improved since the afternoon – it seems to be at its apex of ripeness. The taste is somehow familiar, yet elusive. With every bite I try to place the flavor. Then it hits me: Froot Loops! Tasting it triggers a recollection of how, as a child, I’d use my allowance to buy boxes of Froot Loops. I’d sneak away and covertly eat bowlfuls in bed under the covers while reading Archie by flashlight. Soon all that remains is the skeleton of a chempedak at my feet. I’ve eaten it all, my hands tearing it apart, the fleshy globules offering themselves to me. I can still feel fructose crystals coating my teeth like icing.”

I had entered the temple. Luckily, within a few days, I snapped out of my temporary fruit insanity. Realizing that I too believed in infinity, I came to accept the impossibility of experiencing every fruit out there. The recognition that fruits are never-ending was a sweet release from the need to find them all. From then on I could focus on what I needed to do: tell the story of fruits and humans.

AEB: The impression one gets from

The Fruit Hunters is that the world of the fruit-obsessed is a world of raw fruitists. Is the world of ultraexotics necessarily edenic? Is there another fruit underground, one obsessed not only with exotica but with cooking, preparing, or otherwise transforming their finds?

AG: Yes, and her name is Michelle Marek, bless her soul. [Aw, shucks!--ed.]

AEB: In the book’s discussion of the modern marketing of fruit, you point out that analysts create pie charts to detail the percentages of consumers who like their fruit “firm, soft, juicy, tangy, sweet, dry or moist.” Conspicuously, “ripe” is missing from this list. Is this because “ripe” would place control back in the

hands of farmers and put fruit marketers out of a job? Pardon the

Sex and the City-like phrasing, but is “ripe” the new ultraexotic?

AG: Yes! Although fruit marketers do come up with interesting fruit slogans like “delicious handful of goodness” or “the snack that quenches,” so they aren’t all bad.

AEB: On a related note: The percentage of the general populace who have tasted a ripe fruit off the tree is abysmally low. Is there any hope of de-exoticizing ripeness? Is there any hope of there being a future demographic known as Generation Fruit, one that places a high priority on ripeness and seasonality? What would it take to get there? An apple tree in every yard?

AG: You are speaking of nothing less than a fruit revolution. Could it happen? I hope so! Generation Fruit sounds like a sweet, strange generation. Whether or not we can reclaim seasonality remains to be seen. It’s imperative that we continue supporting local farming communities, but what about bananas, mangos, pineapples, citrus fruits, etc? Buying them in coming years will offer crucial support to developing nations, with their economies dependent on agricultural exports. But what about all the oil needed to transport and grow them? As Generation Fruit knows, solving the food crisis entails solving the fuel crisis. Are Montrealers prepared to give up fruits for eight months of the year? Fruits don’t grow here between November and June. How will members of the progressive community get their five-a-day fix of different colored fruits? It’ll be interesting to see what posterity has up its sleeve. Fruit trees instead of manicured lawns would be an excellent start. To eat the best fruit you need to grow your own. Kids: plant the seeds now! Join Generation Fruit! Who knows how things will change? Nobody could have predicted five years ago that miracle fruits would become a flavor-tripping trend sweeping the nation. The point is, things are always changing. Despite the doomers prognostications, maybe we’ll find viable alternatives to fossil fuels. I hope that Generation Fruit will find a way.

AEB: In the book, you mention returning underwhelming fruit to supermarkets for a refund. Do you think this practice might encourage the large supermarket chains to source better fruit? Is that possible on such a large scale? Do people even want good fruit? (I’m thinking of the “peach breeder for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture” who likes his peaches crispy.) Is it possible to get beyond convenience?

AG: Some people like their peaches crunchy. I don’t think they’ve ever tasted a proper peach; certainly not anything like those Baby Crawfords the three of us sampled in Morgan Hill a few years ago. There are some innovative breeders, like the Zaiger family, who are working on improving the fruits we eat in our supermarket chains. Floyd Zaiger is convinced that good fruits can be mass-produced. As he told me, “If we look hard enough, we will find them.” He creates hybrid fruits in an all-natural way, without any genetic modification, simply by mixing flowers together, birds-and-bees style. I don’t write off all commercial fruits. Honeycrisp apples and Tulameen raspberries are pretty good, aren’t they? I think things have improved in many ways over the past century. Ask your grandparents what fruits they ate in their childhood: most of them didn’t have any fresh fruits. An orange was an inconceivable luxury. Bananas were rarer than blond morels. I do like the idea of returning subpar fruits and getting a refund, although I don’t ever do this at Jean Talon. Big stores, however, always comply. It sends a message. Plus it’s kind of like the fruit-world equivalent of “culture jamming.” Perhaps soon we’ll see Generation Fruit flash mobs.

AEB: What’s your own personal fruit holy grail, the one that got away, the one that’s still out there?

AG: For me, it’s the paradise nut. It’s a fruit container that looks like a bran muffin. It contains seeds that apparently taste like Brazil nuts, only far superior. They’re called sapucaias in Portuguese. They were proof, to early European missionaries, that Brazil was literally paradise on Earth. Even though these paradise nuts captivated me from the start of this fruit adventure, I never did end up tasting one. I’m ok with it, though. As Emily Dickinson once wrote, sagely: “Heaven is what I cannot reach! The Apple on the Tree.”

Adam Gollner brings the miracle of fruit, if not the miracle fruit, to the Montreal launch of The Fruit Hunters, Thursday, June 5, 2008, 7:00-9:00 PM, at the Librairie Drawn & Quarterly (211 Bernard West, Montreal).

For more information: (514) 279-0691.aj

* Rough translation: "The site where the savages make dried raspberries and blueberries annually."

** The "noted gourmand" was Walter Benjamin. His essay "Food" was originally published in 1930. Occasionally Benjamin liked to quote himself in his essays, attributing these citations to "a perceptive critic," or something to that effect.

fig. 1: Le Plateau PDC

fig. 1: Le Plateau PDC